By CAC2 Student Member Nikki Lyons

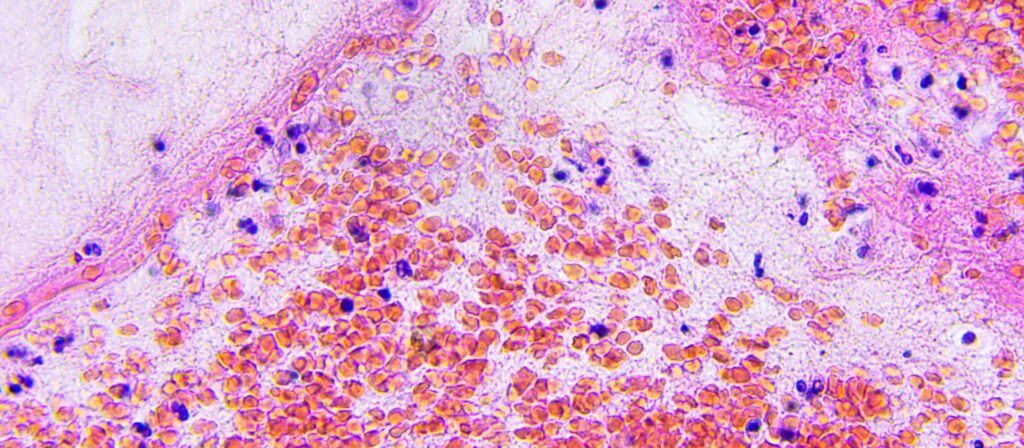

I always knew I wanted to be a scientist. This meant that when I was younger, I loved watching movies and shows featuring some scientific aspect. Their endless supplies of anything they could possibly need, the sparks of brilliance and the immediacy of working experience piqued an interest but were as far from the truth of the scientific process as they could be. Science is slow and arduous; it can go wrong at any step of the way. The first steps of science are pretty simple, observe something you’re interested in and ask a question about it. Next, you need funding and supplies. Funding is often in short supply in pediatric oncology, but there are times you’re lucky and find enough. Materials are next, normally these materials are already in the lab or ordered. Except for tissue. Tissue comes in all types and from all types of organisms, but it is a finite resource. And absolutely necessary. If an experiment calls for tissue, no matter how small the amount, there is no substitute for it. This can create a huge obstacle for research advances. Science is slow enough to begin with, having the process held up any more is not ok. Especially in oncological research, where translating your findings as quickly as possible into treatments can have a direct impact on lives. The more rare the disease, the less tissue there is available. Rare doesn’t mean less devastating or less deserving of research. But it can mean impeded research.

I ran into this problem at my first ever research position. My first independent project was going to be on a rare pediatric brain tumor called a Craniopharyngioma. I thought I was all set to go, I had previous data to work with, funding, and a lab full of supplies. What I was missing was tissue. I first tried ordering the tissue samples of frozen tumors that you “wake up” in the lab. There are several websites to use for this, none of them had what I needed. I then decided to see what others had done in my situation. I read dozens and dozens of papers on this tumor, trying to find recent ones that used tissue rather than retroactive data. Majority of these papers were case studies; they had gotten their tissue directly from a singular patient and that was it. The few articles I found where the authors were in a similar situation, I emailed the authors. I emailed scientists from all over the states, Germany, China, Brazil, and no one had tissue that was available and stored in the correct way to send it to me. This went on for weeks but ultimately my project was scrapped.

This is why Tissue Donation, during treatment and post-mortem is so important. This is why collaborative efforts between groups such as Swifty Foundation, Alex’s Lemonade Stand Foundation, and other CAC2 members are vital. This is why the Gift from a Child program is essential.

Not even close to enough researchers are looking at pediatric brain tumors, there have only been four drugs in over 30 years developed for pediatric patients. There is less focus because they are considered rare. But again, rare does not mean less deserving. We researchers need to listen to the patients and families and start moving the needle forward and faster in regard to breakthroughs. With GFAC changing the culture surrounding post-mortem tissue donation, it means fewer projects scrapped like mine was, better access to tissue, and science turning more quickly into treatments. More lives are saved this way. Since I first wrote about my experience many months ago, the needle has indeed moved toward progress. Many pediatric medicine associations have published papers calling out the need for tissue and putting adequate procedures in place. Patient and family voices have become amplified from hospital boardrooms to the NIH to Congress. Collaborative meetings I have attended at Cure Fest, with CAC2, and Crazy 8 in Philadelphia with Alex’s Lemonade Stand showed us the power of like-minded foundations working together. Our Center of Excellence leaders are publishing more and processing and receiving more tissue donations. Patients are doing better and that’s what matters. Better treatment and the research culture is starting to change and scientists like myself will make sure that this progress will always continue.

Nikki Lyons is a neuroscience and molecular biology student at Columbia University in NYC. She works in research for cancer genetics, patient advocacy, student health, and disability justice. She serves as In the future, she is planning on becoming a pediatric neurosurgeon. Nikki has previously been an intern with the Children’s Brain Tumor Tissue Consortium in Philadelphia and a research assistant at Ann and Robert Lurie Children’s Hospital in Chicago. She currently interns with Swifty Foundation and Gift from a Child and is a Student Member of CAC2.

Nikki currently serves in these leadership positions at Columbia University: Communications Chair |American Medical Women’s Association | Columbia University Premedical Chapter, Disability Policy Representative| General Studies Student Council, Vice President | Psychiatry, Neurology, & Neuropsychiatry Club